7 Field Company War Diary 1917

Source: 7 Field Company War Diary in blue text

149 Inf Bde War Diary

150 Inf Bde War Diary

151 Inf Bde War Diary

Capt J.B. Glubb's Diary - in black text

Capt H.A. Baker's Diary- in brown text

149 Inf Bde War Diary

150 Inf Bde War Diary

151 Inf Bde War Diary

Capt J.B. Glubb's Diary - in black text

Capt H.A. Baker's Diary- in brown text

From the 17th June 1915 until the end of WW1, 7 Field Company RE served with the 50th (Northumbrian Territorial) Division. The Division's three Brigades were 149th,150th and the 151st. At different stages of the war 7 Field Company had supported each of the Brigades. There were three Field Companies RE in the Division:

1st Northumbrian Field Company RE - later changed to 446 Field Company RE

2nd Northumbrian Field Company RE - later changed to 447 Field Company RE.

7th Field Company RE - The only regular unit in the Division

1st Northumbrian Field Company RE - later changed to 446 Field Company RE

2nd Northumbrian Field Company RE - later changed to 447 Field Company RE.

7th Field Company RE - The only regular unit in the Division

1-14 January 1917:

During this period the Company continued to be employed under the III Corps on III Corps tramways with permanent 450 men working parties (B Echelon 7 Coy) a No of petrol tractors up to GL all had been received towards the end of December, enabling further daily tonnage to be carried. Peake Wood - Martinpuich line 103 tons, Bazentin-High Wood line 170 tons. Beyond High Wood all traffic remained hand pushed for the want of tractors. Construction work was much delayed for want of both materials and men. Work carried out by Sections during this period was as follows:-

No1 Section (Lt Chaplin) - general repairs and improvement to the line between Bazentin-High Wood. The heavy hand pushed traffic combined with continued wet weather caused this portion of the line to get in a bad state. Making sidings at Bazentin for loading of stores brought by road. The continuation of the line under construction to connect the Bazentin- High Wood line system to the Peake-Martinpuich line was resumed.

No2 Section (Lt Baker) continued to work as before on the Peake Wood - Martinpuich line Ballasting from Sale Street siding - Martinpuich - Boarding to Gilbert Alley from Gun Pit siding, Ballasting Peake Wood - Bailiff Wood - trench siding at Villa Sta - dugouts at Martinpuich Sta.

No3 Section (2nd Lt Littlewood) preparing line between Flers Switch Dump and Boast trench junction for petrol traction (i.e. Wooden Sleepers at 2' intervals) Straightening the line etc, Loops put in at Flers Switch Dump and 200yds N of Boast Trench Junction.

No4 Section Preparing the line from High Wood station northwards as far as Boast Trench Junction ( i.e. same as done by No3 Section) Loops and general improvement on the Boast Trench Junction - Turks Lane section. On the 15th the O.C. Proceeded on leave, Capt Glubb commanding in his absence.

During this period the Company continued to be employed under the III Corps on III Corps tramways with permanent 450 men working parties (B Echelon 7 Coy) a No of petrol tractors up to GL all had been received towards the end of December, enabling further daily tonnage to be carried. Peake Wood - Martinpuich line 103 tons, Bazentin-High Wood line 170 tons. Beyond High Wood all traffic remained hand pushed for the want of tractors. Construction work was much delayed for want of both materials and men. Work carried out by Sections during this period was as follows:-

No1 Section (Lt Chaplin) - general repairs and improvement to the line between Bazentin-High Wood. The heavy hand pushed traffic combined with continued wet weather caused this portion of the line to get in a bad state. Making sidings at Bazentin for loading of stores brought by road. The continuation of the line under construction to connect the Bazentin- High Wood line system to the Peake-Martinpuich line was resumed.

No2 Section (Lt Baker) continued to work as before on the Peake Wood - Martinpuich line Ballasting from Sale Street siding - Martinpuich - Boarding to Gilbert Alley from Gun Pit siding, Ballasting Peake Wood - Bailiff Wood - trench siding at Villa Sta - dugouts at Martinpuich Sta.

No3 Section (2nd Lt Littlewood) preparing line between Flers Switch Dump and Boast trench junction for petrol traction (i.e. Wooden Sleepers at 2' intervals) Straightening the line etc, Loops put in at Flers Switch Dump and 200yds N of Boast Trench Junction.

No4 Section Preparing the line from High Wood station northwards as far as Boast Trench Junction ( i.e. same as done by No3 Section) Loops and general improvement on the Boast Trench Junction - Turks Lane section. On the 15th the O.C. Proceeded on leave, Capt Glubb commanding in his absence.

14 - 28 January 1917:

During this period the Sections remained employed on the same work as has been given above for the first half of the month. A large number of loops were put in between High Wood and Eaucourt L' Abbaye and between High Wood and Factory Corner, with a view to running regular motor engine traffic to the above rail heads with rations for the trenches with the same object, the line through Martinpuich station was relaid, ballasted heavily with brick Ballast, and extended to two hundred yards in front of Dead Mule Corner. A certain amount of annoyance was caused in camp during this period, by the attentions chiefly nocturnal, of the 4 inch high velocity gun, which however caused no casualties. In the Company a more serious development was the arrival of two 13.5 inch naval gun shells one of which on the 25th fell beside the officer huts completely destroying the latter and ripping large holes through all the huts in camp, luckily the Sappers were all out on their works so no casualties.

29 -31 January 1917:

The Company marched out of billet near Bazentin Le Petit to Rue des Illieux, Albert, the officers being in Rue de Bapaume being already In the best area.The mounted Section remained on their old billet near Becourt, profiting by a few days rest. Time was immediately devoted to drill marching, and Section field work, practice as hard as the hardness of the frost would allow.

During this period the Sections remained employed on the same work as has been given above for the first half of the month. A large number of loops were put in between High Wood and Eaucourt L' Abbaye and between High Wood and Factory Corner, with a view to running regular motor engine traffic to the above rail heads with rations for the trenches with the same object, the line through Martinpuich station was relaid, ballasted heavily with brick Ballast, and extended to two hundred yards in front of Dead Mule Corner. A certain amount of annoyance was caused in camp during this period, by the attentions chiefly nocturnal, of the 4 inch high velocity gun, which however caused no casualties. In the Company a more serious development was the arrival of two 13.5 inch naval gun shells one of which on the 25th fell beside the officer huts completely destroying the latter and ripping large holes through all the huts in camp, luckily the Sappers were all out on their works so no casualties.

29 -31 January 1917:

The Company marched out of billet near Bazentin Le Petit to Rue des Illieux, Albert, the officers being in Rue de Bapaume being already In the best area.The mounted Section remained on their old billet near Becourt, profiting by a few days rest. Time was immediately devoted to drill marching, and Section field work, practice as hard as the hardness of the frost would allow.

9 - 12 January 1917: Very cold, north wind, trying to snow. We attacked at Beaumont Hamel. Heavy bombardment ever since. McQueen has been gazetted a major.

14 January 1917: We were woken up at 1 a.m. By shelling. A 15-cm high-velocity gun kept dropping shells around, for three-quarters of an hour. One landed about twenty yards away and another on the next camp, occupied by the 7th Durham Light Infantry. This gun simply drops shells around anywhere, so there is no use changing one"s position. One landed twenty yards away in the 2nd Northumbrian Field Company's camp, and a dud entered one of the 7th D.L.I.'s huts about twenty yards on the other side. The drivers stood to their horses. I went out to look round while the shelling was going on, and noticed that the sentry did not seem to be about. On further investigation, I found him sitting over a fire in the guard hut. It was Sapper Harman , a boy in No 2 Section. I spoke to him at office next day, put dismissed him without a punishment after a (probably very laughable) harangue . These young fellows with a month or two of training and just come out to France, do not realize the military importance of sentry duty, especially when not in the very presence of the enemy . ·

The Somme battlefield has been very badly cleaned up as compared with some. Off the tracks, one frequently comes on old corpses all through the winter. There used to be a lot of corpses lying in rows on a piece of ground a few hundred yards to the left of the Bazentin -Martinpuich road. When an officer from Army Headquarters came down to see our work and I was obliged to show him round, I took him past the place. I thought it would do him good to see that there was a war on.

The sappers paraded for work all through the winter at 7.45 a.m., so I was called by Donaghie, my batman, at about seven, when he would stumble into my hut and light a candle, and try and break the ice in my tin washbasin. It was no·easy matter to keep warm in bed, and I always slept with all the clothes I possessed heaped on top of me.Dressing was accomplished at full speed,for the longer one took, the more numb did one's fingers become, so that it was impossible to do up buttons. Often my boots were frozen hard as boards, and had to be thawed before I could get into them. About 7.30 a.m., I rushed into the mess for breakfast, to find nothing ready . Then Baker would come in,' vainly trying to buckle his belt with frozen fingers. Eventually at 7.40 a.m., I got a greasy piece of bacon on a tin plate. Sometimes the bread was frozen so hard that it could not be cut with a knife and tasted cold in the mouth like ice-cream. Suddenly the sergeant-major outside blows two blasts on the whistle - five minutes to parade. The sappers gather in a crowd, waiting to fall in. Just at this moment, the tea comes in too hot to drink. From outside, the voice of the sergeant-major calls 'Markers', and then, 'Fall in'. We step out of the hut, assuming stern and martial faces suitable for parade.Section sergeants call their sections to attention and call the roll, and then the sergeant-major collects reports. Sergeant Watkinson, who is always in a bad temper, says surlily, 'All present, sir!' Sergeant Farrar who stammers, after violent contortions of the face, suddenly blurts out, 'Er-dy-all present, sir.' Sergeant Bones, quietly and sedately, 'All present, sir.' Corporal Cheale , who always roars like a bull of Basan, 'ALL PRESENT, SIR.' The sergeant-major turns to Ilfe and says, 'Company report all present, sir. ' I repiy, 'Stand at ease, please, and then give the order, 'March off, please '. Section officers salute like crossing sweepers receiving a sixpenny tip, except for Littlewood , who has just come from Chatham and salutes like the Grenadier Guards.

On the conclusion of this grand military spectacle, I look into the company office dugout, to find a tray piled with papers.Rum jars, Return of Mark it, quarter-master- sergeant to note. Very lights, Return of Dubbin, Indents for. Mark it C.Q .M.S.

Then divisional routine orders, The G.O.C. notes with regret ... Mark it for company orders.Then a document from His Majesty the King, to Sir Douglas Haig, 'It is with the greatest satisfaction that the news of . . . gallant troops .. . road to final victory.' Then Sir Douglas Haig's reply. 'I desire to tender the thanks of the army under my command blah, blah, blah . .. to final victory.' Mark it company notice board. At length, fleeing from the office, I seize my steel helmet and gas mask and set out for my morning walk. Sometimes I look at both tramlines, by walking across on the road from Martinpuich to High Wood, but as a rule I take alternate days for each sector.

Firstly, however, I probably look in on the tramway office, between us and Bazentin-le-Petit, to see my old friend, Good, the most good-natured old man I ever hope to

meet. He wants me to explain the use of some weird pasty yellow mess in a tin with a high odour, which Rimbod has just bought for their mess. Good is in charge of traffic up to High Wood, and has his whole time-table worked out like a real Bradshaw. Often he could be seen hastening out and inscribing in chalk on an idle-looking truck 2 p.m. train.Three hours later, he would stroll out and rub it off, the local wits having meanwhile written underneath I don't think or What abaht it? Nevertheless it was really marvellous the number of trains he sent up the line, the tons of ammunition, engineer stores and rations. His two or three little tractors were going up and down nearly all day. The line in front of High Wood was all pushed by hand, because it was all in full view after Rutherford Alley, and was only used after dark. Rations for the brigade in the line would now come up on the broad gauge to Bazentin and here a covey of quartermasters would collect every afternoon, while the rations were loaded on to the tramline. At 4 p.m. out would walk old Good, full of importance, to start off his 4 p.m. ration train, consisting of a couple of big well-wagons, drawn by a petrol motor tractor. The quarter-blokes would all climb innocently on top, hoping to get a ride. But the tractor invariably stuck as soon as the line started climbing the slope to High Wood. The steep gradient was accomplished at one mile an hour, especially if there was a frost. All the quarter-blokes finished up pushing like mad behind, while a man walked in front putting sand on the lines. A source of never-failing recreation to the infantry pushing parties was to sit on top of the trolleys and run down hill. They used to tear down the slope from High Wood at a huge speed, shouting and yelling like school children. This was a most dangerous and illegal performance, at which I remember at least one man breaking a leg. Good luckily realized the humour as fully as anyone. How we have laughed together. The traffic on the forward portion of the line was under a certain Lieutenant Rudge, who dwelt at High Wood. He was a voluble talker, and, on the arrival of the ration train, would be heard to hold forth something as follows, rushing up and down all the time: 'Hello, what are you doing there with those trucks? .. . Oh yes, you 're the 5th Borders ....

14 January 1917: We were woken up at 1 a.m. By shelling. A 15-cm high-velocity gun kept dropping shells around, for three-quarters of an hour. One landed about twenty yards away and another on the next camp, occupied by the 7th Durham Light Infantry. This gun simply drops shells around anywhere, so there is no use changing one"s position. One landed twenty yards away in the 2nd Northumbrian Field Company's camp, and a dud entered one of the 7th D.L.I.'s huts about twenty yards on the other side. The drivers stood to their horses. I went out to look round while the shelling was going on, and noticed that the sentry did not seem to be about. On further investigation, I found him sitting over a fire in the guard hut. It was Sapper Harman , a boy in No 2 Section. I spoke to him at office next day, put dismissed him without a punishment after a (probably very laughable) harangue . These young fellows with a month or two of training and just come out to France, do not realize the military importance of sentry duty, especially when not in the very presence of the enemy . ·

The Somme battlefield has been very badly cleaned up as compared with some. Off the tracks, one frequently comes on old corpses all through the winter. There used to be a lot of corpses lying in rows on a piece of ground a few hundred yards to the left of the Bazentin -Martinpuich road. When an officer from Army Headquarters came down to see our work and I was obliged to show him round, I took him past the place. I thought it would do him good to see that there was a war on.

The sappers paraded for work all through the winter at 7.45 a.m., so I was called by Donaghie, my batman, at about seven, when he would stumble into my hut and light a candle, and try and break the ice in my tin washbasin. It was no·easy matter to keep warm in bed, and I always slept with all the clothes I possessed heaped on top of me.Dressing was accomplished at full speed,for the longer one took, the more numb did one's fingers become, so that it was impossible to do up buttons. Often my boots were frozen hard as boards, and had to be thawed before I could get into them. About 7.30 a.m., I rushed into the mess for breakfast, to find nothing ready . Then Baker would come in,' vainly trying to buckle his belt with frozen fingers. Eventually at 7.40 a.m., I got a greasy piece of bacon on a tin plate. Sometimes the bread was frozen so hard that it could not be cut with a knife and tasted cold in the mouth like ice-cream. Suddenly the sergeant-major outside blows two blasts on the whistle - five minutes to parade. The sappers gather in a crowd, waiting to fall in. Just at this moment, the tea comes in too hot to drink. From outside, the voice of the sergeant-major calls 'Markers', and then, 'Fall in'. We step out of the hut, assuming stern and martial faces suitable for parade.Section sergeants call their sections to attention and call the roll, and then the sergeant-major collects reports. Sergeant Watkinson, who is always in a bad temper, says surlily, 'All present, sir!' Sergeant Farrar who stammers, after violent contortions of the face, suddenly blurts out, 'Er-dy-all present, sir.' Sergeant Bones, quietly and sedately, 'All present, sir.' Corporal Cheale , who always roars like a bull of Basan, 'ALL PRESENT, SIR.' The sergeant-major turns to Ilfe and says, 'Company report all present, sir. ' I repiy, 'Stand at ease, please, and then give the order, 'March off, please '. Section officers salute like crossing sweepers receiving a sixpenny tip, except for Littlewood , who has just come from Chatham and salutes like the Grenadier Guards.

On the conclusion of this grand military spectacle, I look into the company office dugout, to find a tray piled with papers.Rum jars, Return of Mark it, quarter-master- sergeant to note. Very lights, Return of Dubbin, Indents for. Mark it C.Q .M.S.

Then divisional routine orders, The G.O.C. notes with regret ... Mark it for company orders.Then a document from His Majesty the King, to Sir Douglas Haig, 'It is with the greatest satisfaction that the news of . . . gallant troops .. . road to final victory.' Then Sir Douglas Haig's reply. 'I desire to tender the thanks of the army under my command blah, blah, blah . .. to final victory.' Mark it company notice board. At length, fleeing from the office, I seize my steel helmet and gas mask and set out for my morning walk. Sometimes I look at both tramlines, by walking across on the road from Martinpuich to High Wood, but as a rule I take alternate days for each sector.

Firstly, however, I probably look in on the tramway office, between us and Bazentin-le-Petit, to see my old friend, Good, the most good-natured old man I ever hope to

meet. He wants me to explain the use of some weird pasty yellow mess in a tin with a high odour, which Rimbod has just bought for their mess. Good is in charge of traffic up to High Wood, and has his whole time-table worked out like a real Bradshaw. Often he could be seen hastening out and inscribing in chalk on an idle-looking truck 2 p.m. train.Three hours later, he would stroll out and rub it off, the local wits having meanwhile written underneath I don't think or What abaht it? Nevertheless it was really marvellous the number of trains he sent up the line, the tons of ammunition, engineer stores and rations. His two or three little tractors were going up and down nearly all day. The line in front of High Wood was all pushed by hand, because it was all in full view after Rutherford Alley, and was only used after dark. Rations for the brigade in the line would now come up on the broad gauge to Bazentin and here a covey of quartermasters would collect every afternoon, while the rations were loaded on to the tramline. At 4 p.m. out would walk old Good, full of importance, to start off his 4 p.m. ration train, consisting of a couple of big well-wagons, drawn by a petrol motor tractor. The quarter-blokes would all climb innocently on top, hoping to get a ride. But the tractor invariably stuck as soon as the line started climbing the slope to High Wood. The steep gradient was accomplished at one mile an hour, especially if there was a frost. All the quarter-blokes finished up pushing like mad behind, while a man walked in front putting sand on the lines. A source of never-failing recreation to the infantry pushing parties was to sit on top of the trolleys and run down hill. They used to tear down the slope from High Wood at a huge speed, shouting and yelling like school children. This was a most dangerous and illegal performance, at which I remember at least one man breaking a leg. Good luckily realized the humour as fully as anyone. How we have laughed together. The traffic on the forward portion of the line was under a certain Lieutenant Rudge, who dwelt at High Wood. He was a voluble talker, and, on the arrival of the ration train, would be heard to hold forth something as follows, rushing up and down all the time: 'Hello, what are you doing there with those trucks? .. . Oh yes, you 're the 5th Borders ....

Allright .. . . Yes . .. . Splendid .... What? ... Some- one's got one of your trucks? ... Yes, you're the 6th D.L.I. Oh, that's quite all right. Yes, let the 8th have it. Splendid. Yes .... [The 8th was his battalion] Here hi! Hi there! What are you doing with that truck? Put it in here . . .. Oh no. As you were .... You're Beer-one five-0 battery ....All right, yes splendid . Take it away, my lad.' A vivid imitation of which style was given later at a battalion concert when out at rest, and brought the house down. All the poor devils who had been on ration party fatigues at High Wood, applauded enthusiastically Our officers' mess is really very bad at present, no one having the time or the energy to take it in hand. Old Sapper Smart (most unsuitably named) is cook and crawls about with a curved back by way of having rheumatism. Geard, the mess-waiter, is really a good fellow at heart but a bit idle. The only thing they could do was to sing in harmony, the cookhouse being constantly enlivened by the strains of 'Old Folks at Home', or 'My Home in Tennessee'.

At Christmas, we presented them with a bottle of port, which Geard bore away from the mess. On getting outside, however, he apparently thought he had not done the honourable by us, for he appeared round the door again and shaking the bottle at us, as though he were laying us under a curse, he said,, 'Your health, gentlemen', and vanished again looking much embarrassed. Rather touching, I thought. The name Bazentin-le -Petit is a fearful stumbling block to the British army. I have heard it called Bazenteen, Bazentin, Bazentin-le -Pettitt, Petty Bazentin, and Petty basentin. Sergeant Bones always insists on calling it Petty Benzenteen.

Leaving the tramways office at Bazentin, I would walk up to High Wood and then down the slope to Flers switch, and the front line by Eaucourt L'Abbaye, or down the right fork line to the Coughdrop and Turks Road, or alternatively, I would take the track to Martinpuich, and follow the forward tramline to Gilbert Alley and up to opposite Le Sars. A ridge of high ground runs from High Wood through Martinpuich, and everything east of this ridge is in full view of the enemy. Thus throughout most of my walk, I am visible to the Boche. But the distance is too great for a rifle sniper, and their artillery did not normally think it worth while to shoot at two men - my orderly and myself. Having looked at all the men at work, inspected the state of the tramline and perhaps thought of some new ideas, I would get back to camp at about noon, warm at last after a four-hour walk. One day, having visited the northerly line in front of Le Sars, I walked back through Martinpuich . The village was merely an area of vast mounds of debris of earth and broken brick, with wooden beams, shattered bits of furniture or smashed weapons, sticking out at odd angles. The whole countryside was a vast sea of grey mud, over which trailed low grey clouds, discharging a persistent drizzle. No words of mine can describe the dreariness and hopeless desolation of the scene, wrapped in mist and rain. I sat down on a heap of broken brick and rubbish for a few minutes rest. A cold gusty wind blows the driving rain in my face. Just behind me, a torn strip of old curtain, caught between two splintered roof-beams, flaps wearily in the icy wind. Looking away to the left, I can just see through the rainy mist the splintered trees of Eaucourt and further to the left those of Le Sars. The distant ridge is invisible. owing to the grey drizzle . The middle of the picture is occupied by the huge mound of crumbling white stone which was once Martinpuich church. Two tanks, covered with green nets, are hiding just outside the village.

Every now and then, a distant boom is followed by a low whistle, a spurt of grey and, after a few seconds, by a loud incisive Kr-rump, as the 8-inch sail over and burst on the Albert-Bapaume road. Nearby, a green upholstered sofa, stained and soaking, lies on its side, a large hole in the seat allowing the stuffing to hang out. An infantry party, their waterproof sheets glistening on their shoulders, and the drops of rain trembling round the edges of their helmets, slops past with shovels in their hands. They flounder through the mud or try to jump from stone to stone in the ruins, grunting and grumbling in the most abusive language to themselves. Their legs and thighs are encased in sand bags as is the winter custom. They disappear into Gunpit Road and once again there is dampness and silence, except for the flapping piece of curtain and the distant booms.

At Christmas, we presented them with a bottle of port, which Geard bore away from the mess. On getting outside, however, he apparently thought he had not done the honourable by us, for he appeared round the door again and shaking the bottle at us, as though he were laying us under a curse, he said,, 'Your health, gentlemen', and vanished again looking much embarrassed. Rather touching, I thought. The name Bazentin-le -Petit is a fearful stumbling block to the British army. I have heard it called Bazenteen, Bazentin, Bazentin-le -Pettitt, Petty Bazentin, and Petty basentin. Sergeant Bones always insists on calling it Petty Benzenteen.

Leaving the tramways office at Bazentin, I would walk up to High Wood and then down the slope to Flers switch, and the front line by Eaucourt L'Abbaye, or down the right fork line to the Coughdrop and Turks Road, or alternatively, I would take the track to Martinpuich, and follow the forward tramline to Gilbert Alley and up to opposite Le Sars. A ridge of high ground runs from High Wood through Martinpuich, and everything east of this ridge is in full view of the enemy. Thus throughout most of my walk, I am visible to the Boche. But the distance is too great for a rifle sniper, and their artillery did not normally think it worth while to shoot at two men - my orderly and myself. Having looked at all the men at work, inspected the state of the tramline and perhaps thought of some new ideas, I would get back to camp at about noon, warm at last after a four-hour walk. One day, having visited the northerly line in front of Le Sars, I walked back through Martinpuich . The village was merely an area of vast mounds of debris of earth and broken brick, with wooden beams, shattered bits of furniture or smashed weapons, sticking out at odd angles. The whole countryside was a vast sea of grey mud, over which trailed low grey clouds, discharging a persistent drizzle. No words of mine can describe the dreariness and hopeless desolation of the scene, wrapped in mist and rain. I sat down on a heap of broken brick and rubbish for a few minutes rest. A cold gusty wind blows the driving rain in my face. Just behind me, a torn strip of old curtain, caught between two splintered roof-beams, flaps wearily in the icy wind. Looking away to the left, I can just see through the rainy mist the splintered trees of Eaucourt and further to the left those of Le Sars. The distant ridge is invisible. owing to the grey drizzle . The middle of the picture is occupied by the huge mound of crumbling white stone which was once Martinpuich church. Two tanks, covered with green nets, are hiding just outside the village.

Every now and then, a distant boom is followed by a low whistle, a spurt of grey and, after a few seconds, by a loud incisive Kr-rump, as the 8-inch sail over and burst on the Albert-Bapaume road. Nearby, a green upholstered sofa, stained and soaking, lies on its side, a large hole in the seat allowing the stuffing to hang out. An infantry party, their waterproof sheets glistening on their shoulders, and the drops of rain trembling round the edges of their helmets, slops past with shovels in their hands. They flounder through the mud or try to jump from stone to stone in the ruins, grunting and grumbling in the most abusive language to themselves. Their legs and thighs are encased in sand bags as is the winter custom. They disappear into Gunpit Road and once again there is dampness and silence, except for the flapping piece of curtain and the distant booms.

Back at company headquarters after a hasty lunch, I would put on my spurs, my British-warm coat and my gloves, and mount my horse. Minx was utterly dejected by the daily ride to Becourt. It was only about four miles each way, but the cold, the deep mud, and the slippery roads full of holes made it an agony. Running the gauntlet of the guns on the Contalmaison road was a daily terror. There was a battery of 8-inch howitzers there, enormous great old-fashioned guns -the newest 8-inch are about half the size. Owing to the impossibility of moving these heavy guns across country, they had taken up their position beside the road itself. Skirting the edge of Mametz Wood and out on to the Contalmaison road, I was sure to see the noses of the huge howitzers just rising into the firing position and hear a voice like one crying in the wilderness - 'No 1 Gun ready, sir!' Thinking they were just going to fire, I would halt . There

the four guns would sit, their noses. stuck up into the air like frogs, for minutes on end, while I froze colder and colder, and my horse backed round and round and bored at my hand to try and get on. Finally I decide to chance it, and trot rapidly up to get past, blinking madly all the time for fear the thing would suddenly go off. Just as I get up to the first gun, a man appears from a burrow in the mud on my left, raises a megaphone, and shouts, 'No 1Gun, fire!' For a second I see the man on the gun as he pulls the string.Then there is a roar and a flash of flame and the huge old gun seems to rush back about five yards on the recoil. My horse pounds into

the air, and I catch the cry, 'No 2 gun, fire!' just as I get opposite the next one. Eventually I escape at the the end of the four guns, my horse tearing wildly at my numbed fingers, and my ears buzzing. Already the noses of the guns are slowly rising into the air again, and the monotonous voices are again chanting. 'No 1 gun . Two-oh [letter o] minutes more left .' 'Two-oh minutes more left, Sir!' answers the echoing sergeant.

As I vainly try to persuade my horse to come back to a walk down the slippery slope by the corner of Mametz Wood, a still small receding voice comes after me from the distance, 'No 1 gun ready, sir!'

It is my experience that, no matter how warm I start.out, my hands are frozen in five minutes, and my fingers numbed and powerless. If I can find some reasonable ground and can keep trotting, my circulation gradually returns, after a certain amount of painful tingling, and a feeling as if my hands would burst. The mounted section has had an easier time since the tramways have really begun to function. In September, they had a very exhausting period, working literally day and night on the road up to High Wood. A day's work for the wagons meant starting in the dusk before dawn, usually in icy cold, and returning to camp just before dark . They suffered misery all day in the cold weather.The wagons could only move at a walk and frequent traffic blocks kept them halted for long periods. The idea of ever being warm was out of the question. When they came in, horses, harness and men were literally plastered all over with wet, yellow mud. To clean the horses and harness after such a day necessitated about twelve hours work. Each driver had two horses and two sets of harness. Next time the driver's turn came, he was expected to turn out with clean shining horses, and spotless steelwork and soft oiled leatherwork. Inevitably at times, when teams were working every day, horses, harness and men remained coated with wet clay for days on end. The Town Major of Becourt is John Coates, a famous singer. A most conscientious town major he seems to be . A story is told of how he zealously placarded the Becourt camps with neat notice boards To the Latrines, Ablution Benches, Incinerator, Brigade Headquarters and so on, preparatory to an inspection by a senior officer. Unfortunately, the night before the inspection, a humorist of, I believe, 281st Coy.R.E., erected a rival set' of notice boards in a lighter vein, such as This way to the War, pointing up the Contalmaison road, This way to Blighty, pointing along the road to Albert. Arriving at the camp at Becourt, I would probably say a few words to the C.Q.M.S., who lives there, and sign some indents for him, after which I would go down to the stables and talk to the drivers and to my dear old, ever-sympathetic equine friends. Then I remounted my horse and set out once more to return to company headquarters. I was usually cold again by now, and often failed to get warm at all on the way back, as it was now about four o' clock and the evening was drawing in. Then came the pleasant part of the day, when I burst into the mess at about half past four, to a roaring fire, and the others sitting round it, after coming in frozen from their work.Then steaming tin mugs of hot, strong tea from our old tin tea pot, a veteran of many months of war. Plates piled with thick slices of toast (usually wet or burnt, it is true)and ration jam, make a royal meal. Often we also had a cake, either McQueen's, Baker's or mine, sent out by post by loving families at home. After tea, I retired to my little hut, to compose the work tables for the next day, together with lists of stores to be drawn, indents, orders for transport and other routine affairs. Then I would adjourn to the company office to.wade through more trays of administrative routine and sign company orders. Those who have never taken part in wars imagine them to be full of fears, danger and excitement. In reality, such things are comparatively rare interludes: More than anything else, war is work - day and night, wet and dry, cold or hot, monotonous, back aching work. Next to work comes;discomfort, especially to be always cold and wet - at least when the war is in France and Belgium. These characteristics apply as much to the infantry as to gunners and sappers. Every now and again, infantry may be involved in an attack and suffer intense danger and heavy casualties. But, year in year out, infantry also spend most of their time working, repairing their trenches, carrying up rations, stores and ammunition, mending roads to allow their horsed-transport to come up, and endless monotonous, cold, wet and back aching fatigues. Dinner in the mess is not exactly a gourmet repast, but it is enough. Soup made of powder, meat, potatoes and peas out of tins and milk pudding. Sometimes the pudding is varied with one or other of our two savouries - cold sardines on toast or toasted ration cheese. These meals sound good, but they were always the same. The food was usually not hot and everything was dirty. I always ate largely and nobody minded much, except McQueen who was much older than any of us, and Rimbod, the interpreter, who, being a Frenchman, attached more importance to food. In point of fact, there was really nothing for an interpreter to do, as there were no civilian French people within many miles of us . Rimbod spent most of his time trying to get a lift back to the inhabited area, where he could speak French. He justified these forays by returning with a load of gastronomic delicacies, and useful articles - for example he bought me a little iron stove, burning wood, which most efficiently heated my tiny hut. Rimbod was a character in his way. In peace-time he lived in London, and was a member of the Serpentine Swimming club. At one time, we used to drink port wine in the mess. This habit was started in June 1916, when I was in England with my appendix, by the arrival of a case of port wine, as a gift from 'Charlie' Chaplin's father. Just before we came to the Somme another case arrived, but this time it was rather unpleasantly followed by a bill! However, we had by then become accustomed to it and used sometimes to get some from the Expeditionary Force Canteen, The trouble was that everybody used to drink so much of it. Powell, of the Northumberland Field Companies, once came in and drank a tumblerful at 11 a.m.!

One of the vital questions in this bitter cold weather was fuel. The coal and coke issued with the rations was enough for cooking, but no fuel was issued for heating. At first we helped ourselves freely from Mametz Wood, till an order came round to say that no woods were to be touched by troops on any account, on pain of Court Martial. This was a most inhuman order, doubtless issued by some Q. authority, sitting in a comfortable office at the base. The troops were perpetually wet through and could never get warm or dry. To be constantly cold is terribly depressing to morale. All the woods had been well shelled, and a little organization would have made it feasible to issue plenty of wood in the form of splintered branches, twigs and odd pieces. Soon after, however, an officer came with a party of men to cut and remove any serviceable pieces of timber remaining in Mametz Wood. We approached him cautiously on the subject, whereupon he said, 'Oh that's all rot! Send your fellows to me and I'll give them all they want from my choppings every day.' So hence forward we all had roaring fires every night, and the troops were able to get warm and to dry their clothes. In villages further back, the military police will not allow wood to be taken, although the villages are razed to the ground, but the heaps of rubble contain many old broken roof beams or shattered windows. This is said to be because the French will not allow us to touch them, in case there may be a few bits of timber there, which might be useful to them after the war. No-one has any bowels of compassion for poor numbed and shivering Thomas Atkins, knee-deep in mud, in the driving rain on the - Somme. Casualties in the front line from trench feet were at this time enormous, and much more serious than losses from enemy fire. Orders are constantly coming round about it, telling how to grease the feet and socks, and how to rub the feet and dry the socks. Socks must be removed once a day. Funnily enough, a captured German order shows that they are suffering the same as us, but their regulations are exactly contrary to ours. They say that the boots will on no account be removed during the whole period of a spell in the trenches!

18January, 1917: Bitterly cold, and a north wind. Black frost all day long. We were shelled again all night. Just as you are going off to sleep, you wake with a thumping heart, as the shell passes just over your head with the roar of an express train. Then there is a loud bang, a few hundred yards away, somewhere in Mametz Wood. B Echelon had eight casualties.

19January: A heavy fall of snow. Bitterly cold. The ice in the shell holes is bearing. Dressing is almost unbearable agony. Fortunately Chaplin has built a brick fireplace in the officers' mess, so we have pleasant evenings with a fire and a gramophone. The III Corps is to move out to rest. The Anzacs are going to take over. We do not know if we shall come out, or be left to run the tramlines.

25January: When I returned from Becourt this afternoon, Donaghie said to me, 'You've just had a narrow escape, Sir !' On looking at the camp, I saw my own hut in complete ruins, most of the officers' huts damaged, and holes through some of the men 's. Where my hut had been was a colossal shell crater. At 2.30 p.m. there had been a tremendous explosion, identified as a 13.5-inch high velocity gun. Luckily everyone was out working and we had no casualties. B Echelon had one killed and some wounded. The 7th Durhams had three killed and three wounded.

26-27 January: We are going out of the line. I spent these two days in Albert, trying to get billets. Luckily I found that Firbank, whom I knew at Cheltenham, was assistant Town Major, and I succeeded in getting some very good billets. On 28 January, No 2 Section marched in to Albert, as I wanted to get the billets occupied , before anyone else moved in to them, especially as the Anzacs are arriving to take over the front line. On 29th, the remainder of the company marched into Albert. They marched very well and looked fine, considering they have been five months in the forward area, knee-deep in mud.

the four guns would sit, their noses. stuck up into the air like frogs, for minutes on end, while I froze colder and colder, and my horse backed round and round and bored at my hand to try and get on. Finally I decide to chance it, and trot rapidly up to get past, blinking madly all the time for fear the thing would suddenly go off. Just as I get up to the first gun, a man appears from a burrow in the mud on my left, raises a megaphone, and shouts, 'No 1Gun, fire!' For a second I see the man on the gun as he pulls the string.Then there is a roar and a flash of flame and the huge old gun seems to rush back about five yards on the recoil. My horse pounds into

the air, and I catch the cry, 'No 2 gun, fire!' just as I get opposite the next one. Eventually I escape at the the end of the four guns, my horse tearing wildly at my numbed fingers, and my ears buzzing. Already the noses of the guns are slowly rising into the air again, and the monotonous voices are again chanting. 'No 1 gun . Two-oh [letter o] minutes more left .' 'Two-oh minutes more left, Sir!' answers the echoing sergeant.

As I vainly try to persuade my horse to come back to a walk down the slippery slope by the corner of Mametz Wood, a still small receding voice comes after me from the distance, 'No 1 gun ready, sir!'

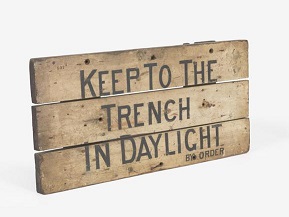

It is my experience that, no matter how warm I start.out, my hands are frozen in five minutes, and my fingers numbed and powerless. If I can find some reasonable ground and can keep trotting, my circulation gradually returns, after a certain amount of painful tingling, and a feeling as if my hands would burst. The mounted section has had an easier time since the tramways have really begun to function. In September, they had a very exhausting period, working literally day and night on the road up to High Wood. A day's work for the wagons meant starting in the dusk before dawn, usually in icy cold, and returning to camp just before dark . They suffered misery all day in the cold weather.The wagons could only move at a walk and frequent traffic blocks kept them halted for long periods. The idea of ever being warm was out of the question. When they came in, horses, harness and men were literally plastered all over with wet, yellow mud. To clean the horses and harness after such a day necessitated about twelve hours work. Each driver had two horses and two sets of harness. Next time the driver's turn came, he was expected to turn out with clean shining horses, and spotless steelwork and soft oiled leatherwork. Inevitably at times, when teams were working every day, horses, harness and men remained coated with wet clay for days on end. The Town Major of Becourt is John Coates, a famous singer. A most conscientious town major he seems to be . A story is told of how he zealously placarded the Becourt camps with neat notice boards To the Latrines, Ablution Benches, Incinerator, Brigade Headquarters and so on, preparatory to an inspection by a senior officer. Unfortunately, the night before the inspection, a humorist of, I believe, 281st Coy.R.E., erected a rival set' of notice boards in a lighter vein, such as This way to the War, pointing up the Contalmaison road, This way to Blighty, pointing along the road to Albert. Arriving at the camp at Becourt, I would probably say a few words to the C.Q.M.S., who lives there, and sign some indents for him, after which I would go down to the stables and talk to the drivers and to my dear old, ever-sympathetic equine friends. Then I remounted my horse and set out once more to return to company headquarters. I was usually cold again by now, and often failed to get warm at all on the way back, as it was now about four o' clock and the evening was drawing in. Then came the pleasant part of the day, when I burst into the mess at about half past four, to a roaring fire, and the others sitting round it, after coming in frozen from their work.Then steaming tin mugs of hot, strong tea from our old tin tea pot, a veteran of many months of war. Plates piled with thick slices of toast (usually wet or burnt, it is true)and ration jam, make a royal meal. Often we also had a cake, either McQueen's, Baker's or mine, sent out by post by loving families at home. After tea, I retired to my little hut, to compose the work tables for the next day, together with lists of stores to be drawn, indents, orders for transport and other routine affairs. Then I would adjourn to the company office to.wade through more trays of administrative routine and sign company orders. Those who have never taken part in wars imagine them to be full of fears, danger and excitement. In reality, such things are comparatively rare interludes: More than anything else, war is work - day and night, wet and dry, cold or hot, monotonous, back aching work. Next to work comes;discomfort, especially to be always cold and wet - at least when the war is in France and Belgium. These characteristics apply as much to the infantry as to gunners and sappers. Every now and again, infantry may be involved in an attack and suffer intense danger and heavy casualties. But, year in year out, infantry also spend most of their time working, repairing their trenches, carrying up rations, stores and ammunition, mending roads to allow their horsed-transport to come up, and endless monotonous, cold, wet and back aching fatigues. Dinner in the mess is not exactly a gourmet repast, but it is enough. Soup made of powder, meat, potatoes and peas out of tins and milk pudding. Sometimes the pudding is varied with one or other of our two savouries - cold sardines on toast or toasted ration cheese. These meals sound good, but they were always the same. The food was usually not hot and everything was dirty. I always ate largely and nobody minded much, except McQueen who was much older than any of us, and Rimbod, the interpreter, who, being a Frenchman, attached more importance to food. In point of fact, there was really nothing for an interpreter to do, as there were no civilian French people within many miles of us . Rimbod spent most of his time trying to get a lift back to the inhabited area, where he could speak French. He justified these forays by returning with a load of gastronomic delicacies, and useful articles - for example he bought me a little iron stove, burning wood, which most efficiently heated my tiny hut. Rimbod was a character in his way. In peace-time he lived in London, and was a member of the Serpentine Swimming club. At one time, we used to drink port wine in the mess. This habit was started in June 1916, when I was in England with my appendix, by the arrival of a case of port wine, as a gift from 'Charlie' Chaplin's father. Just before we came to the Somme another case arrived, but this time it was rather unpleasantly followed by a bill! However, we had by then become accustomed to it and used sometimes to get some from the Expeditionary Force Canteen, The trouble was that everybody used to drink so much of it. Powell, of the Northumberland Field Companies, once came in and drank a tumblerful at 11 a.m.!

One of the vital questions in this bitter cold weather was fuel. The coal and coke issued with the rations was enough for cooking, but no fuel was issued for heating. At first we helped ourselves freely from Mametz Wood, till an order came round to say that no woods were to be touched by troops on any account, on pain of Court Martial. This was a most inhuman order, doubtless issued by some Q. authority, sitting in a comfortable office at the base. The troops were perpetually wet through and could never get warm or dry. To be constantly cold is terribly depressing to morale. All the woods had been well shelled, and a little organization would have made it feasible to issue plenty of wood in the form of splintered branches, twigs and odd pieces. Soon after, however, an officer came with a party of men to cut and remove any serviceable pieces of timber remaining in Mametz Wood. We approached him cautiously on the subject, whereupon he said, 'Oh that's all rot! Send your fellows to me and I'll give them all they want from my choppings every day.' So hence forward we all had roaring fires every night, and the troops were able to get warm and to dry their clothes. In villages further back, the military police will not allow wood to be taken, although the villages are razed to the ground, but the heaps of rubble contain many old broken roof beams or shattered windows. This is said to be because the French will not allow us to touch them, in case there may be a few bits of timber there, which might be useful to them after the war. No-one has any bowels of compassion for poor numbed and shivering Thomas Atkins, knee-deep in mud, in the driving rain on the - Somme. Casualties in the front line from trench feet were at this time enormous, and much more serious than losses from enemy fire. Orders are constantly coming round about it, telling how to grease the feet and socks, and how to rub the feet and dry the socks. Socks must be removed once a day. Funnily enough, a captured German order shows that they are suffering the same as us, but their regulations are exactly contrary to ours. They say that the boots will on no account be removed during the whole period of a spell in the trenches!

18January, 1917: Bitterly cold, and a north wind. Black frost all day long. We were shelled again all night. Just as you are going off to sleep, you wake with a thumping heart, as the shell passes just over your head with the roar of an express train. Then there is a loud bang, a few hundred yards away, somewhere in Mametz Wood. B Echelon had eight casualties.

19January: A heavy fall of snow. Bitterly cold. The ice in the shell holes is bearing. Dressing is almost unbearable agony. Fortunately Chaplin has built a brick fireplace in the officers' mess, so we have pleasant evenings with a fire and a gramophone. The III Corps is to move out to rest. The Anzacs are going to take over. We do not know if we shall come out, or be left to run the tramlines.

25January: When I returned from Becourt this afternoon, Donaghie said to me, 'You've just had a narrow escape, Sir !' On looking at the camp, I saw my own hut in complete ruins, most of the officers' huts damaged, and holes through some of the men 's. Where my hut had been was a colossal shell crater. At 2.30 p.m. there had been a tremendous explosion, identified as a 13.5-inch high velocity gun. Luckily everyone was out working and we had no casualties. B Echelon had one killed and some wounded. The 7th Durhams had three killed and three wounded.

26-27 January: We are going out of the line. I spent these two days in Albert, trying to get billets. Luckily I found that Firbank, whom I knew at Cheltenham, was assistant Town Major, and I succeeded in getting some very good billets. On 28 January, No 2 Section marched in to Albert, as I wanted to get the billets occupied , before anyone else moved in to them, especially as the Anzacs are arriving to take over the front line. On 29th, the remainder of the company marched into Albert. They marched very well and looked fine, considering they have been five months in the forward area, knee-deep in mud.

30 January - 8 February: In billets in Albert. The sappers doing drill and route marching. They drill extremely well, considering that it is their first attempt for five months, and that during that time we have had many casualties and many reinforcements. All buttons and equipment have been polished up, and the troops are very cheerful. The cold all this time was bitter, the north wind simply cutting off one's nose and ears. The ground is frozen as hard as iron, and all water is solid ice. There is still a little powdery snow in the streets and on the north side of houses and walls. The drivers are reduced to exercising every morning in a ring in a field behind the stables. Horses exercising are not allowed on the roads , which are always jammed with t raffic, and the earth tracks, which were deep in mud in December, have now frozen into cast iron ruts and holes, so as to be almost unrideable. The drivers also played a few games of soccer, the first this year, though the ground was rather hard for falling. I was sporting enough (!) to play myself once, much against my inclinations, though I actually enjoyed it a certain amount. However I made a complete ass of myself being opposed to Driver Nixon, who was much too good for me, seeing that I have practically, never played soccer in my life.

The cold all this time was bitter, with a cutting north wind. My daily ride from Albert to Becourt and back to see the horses was agony. The camp at Becourt, however, is really much improved since the frost as, instead of literally sinking to one's knees in mud, one walks on ground as hard and dry as iron, though it is difficult to stand up on it, as it is frozen into the ridges and ruts formed in the mud.

The cold all this time was bitter, with a cutting north wind. My daily ride from Albert to Becourt and back to see the horses was agony. The camp at Becourt, however, is really much improved since the frost as, instead of literally sinking to one's knees in mud, one walks on ground as hard and dry as iron, though it is difficult to stand up on it, as it is frozen into the ridges and ruts formed in the mud.

I tried to get two Nissen huts for the drivers a month or so ago, but was told it was not worth while, as we would be moving soon. We had two company concerts in Albert, both of which were good. At these entertainments, the correct procedure is for the officers to go for the first half of the programme. They sit on broken chairs or ration-boxes, sipping beer out of tin mugs, though sometimes champagne is provided, locally purchased at three francs a bottle. The songs, while the officers are present, are usually of the sentimental variety, such as, 'Sweetheart when I lost you', 'Thora', or 'Some where a voice is calling. ' Or a few rousing old; l stagers like 'John Peel', sung this time by Sapper Clarke, a Cumberland man. Sometimes we have 'There is a tavern in the town', or a good old army rouser, like 'Three cheers for the red, white and blue'. At one of the Albert concerts, Sapper Manning, the company tailor, very refined and late of, Selfridge's, sang 'Kathleen Mavourneen'. We have hardly been able to get any beer the whole winter on the Somme. The nearest place where it could be got was Corbie, a forty-mile round trip for a wagon, and all our transport was working day and night up the line. However we got some for these two concerts . When the officers had left, things warmed up, judging by the roaring sound of singing, perhaps due to the unaccustomed joys of free beer, paid for out of the canteen fund.

One of the troubles about concerts is how to get away. Finally the officers make up their minds that honour is satisfied, but their first attempt to retire is prevented by a nervous sergeant, who haltingly offers the conventional thanks to the officers. Then comes the awful moment when an equally nervous officer has to stand up and reply. It was allright at the first concert, as McQueen was there and 'said a few apt words', which I believe he quite enjoys. Then, to my horror, Corporal MacLaren stood up and called out, 'Three cheers for the captain.' But as McQueen was just going out, I merely blushed and fled. I was so embarrassed at being cheered that I stayed away from the second concert, lest it should happen again.

On one occasion, the officers actually made a contribution. Baker and Chaplin brought the officers' mess gramophone and played 'I want to be a sailor', sung by Harry Lauder, a really fine tune. The officers had a fairly decent billet in Rue de Bapaume in Albert - or at least it seemed so, as we had not been in a house for nearly five months. The billet was in a large house, part of which had once been an estaminet. We had our mess in a small room behind the estaminet, where we erected a stove made from an oil-drum. Baker, Charles (Chaplin) and I commenced by sleeping in the estaminet, which had a brick floor and a broken plate-glass window covering the whole street front. The cold was unendurable, so we moved to a once rather smart salon in the other part of the house. Here there was a fireplace and we had a good fire at night, Baker running out for fuel when it got low. Before we left the billet, we had burned most of the back stairs. Luckily the weather was dry as, though there was a ceiling on our room, a shell had burst in the room above and blown off the roof of the house. The house had once been used by the Town Major, who had left it in a filthy state - he whose chief job is to see that other people leave clean billets. The back garden is honeycombed with deep dugouts, constructed to harbour the gallant Town Major, in case Albert was shelled last July he had it most elegantly fitted up with gilded furniture, mirrors and green curtains. Our batmen decided to sleep there, as we preferred to be above ground, even if frozen, owing to the rats who had moved in when the Town Major moved out.The upstairs rooms in the house present the usual desolation of such apartments in these abandoned towns. The floor is strewn thick with every kind of debris, ladies', dresses, books, newspapers, toys, hats, beams blown down and splintered from the gaping roof, broken chairs, mixed and ground up with plaster and dirt. The only furniture left is a shattered chest-of-drawers, and a jagged-holed wardrobe lying on its face. We imported some green garden chairs into the room we occupied and, with Baker and Chaplin ministering to the fire, we managed to sleep unfrozen, and even to have an occasional wash. Getting up in the morning, however, was bitter, and, going out of doors, the north wind came blowing fine dust along the frozen street, stinging one's nose and ears until they ached.

The company was billeted in the Piffre factory, which had a large yard, where the troops drilled. Normally we had drill and training lectures on one day, and a route march on the next. These marches were highly scientific affairs. In front strode McQueen, his hands behind his back. As he is unable to take a pace of less than a

yard and a half, he finds it extremely difficult himself to keep in step with the men

One of the troubles about concerts is how to get away. Finally the officers make up their minds that honour is satisfied, but their first attempt to retire is prevented by a nervous sergeant, who haltingly offers the conventional thanks to the officers. Then comes the awful moment when an equally nervous officer has to stand up and reply. It was allright at the first concert, as McQueen was there and 'said a few apt words', which I believe he quite enjoys. Then, to my horror, Corporal MacLaren stood up and called out, 'Three cheers for the captain.' But as McQueen was just going out, I merely blushed and fled. I was so embarrassed at being cheered that I stayed away from the second concert, lest it should happen again.

On one occasion, the officers actually made a contribution. Baker and Chaplin brought the officers' mess gramophone and played 'I want to be a sailor', sung by Harry Lauder, a really fine tune. The officers had a fairly decent billet in Rue de Bapaume in Albert - or at least it seemed so, as we had not been in a house for nearly five months. The billet was in a large house, part of which had once been an estaminet. We had our mess in a small room behind the estaminet, where we erected a stove made from an oil-drum. Baker, Charles (Chaplin) and I commenced by sleeping in the estaminet, which had a brick floor and a broken plate-glass window covering the whole street front. The cold was unendurable, so we moved to a once rather smart salon in the other part of the house. Here there was a fireplace and we had a good fire at night, Baker running out for fuel when it got low. Before we left the billet, we had burned most of the back stairs. Luckily the weather was dry as, though there was a ceiling on our room, a shell had burst in the room above and blown off the roof of the house. The house had once been used by the Town Major, who had left it in a filthy state - he whose chief job is to see that other people leave clean billets. The back garden is honeycombed with deep dugouts, constructed to harbour the gallant Town Major, in case Albert was shelled last July he had it most elegantly fitted up with gilded furniture, mirrors and green curtains. Our batmen decided to sleep there, as we preferred to be above ground, even if frozen, owing to the rats who had moved in when the Town Major moved out.The upstairs rooms in the house present the usual desolation of such apartments in these abandoned towns. The floor is strewn thick with every kind of debris, ladies', dresses, books, newspapers, toys, hats, beams blown down and splintered from the gaping roof, broken chairs, mixed and ground up with plaster and dirt. The only furniture left is a shattered chest-of-drawers, and a jagged-holed wardrobe lying on its face. We imported some green garden chairs into the room we occupied and, with Baker and Chaplin ministering to the fire, we managed to sleep unfrozen, and even to have an occasional wash. Getting up in the morning, however, was bitter, and, going out of doors, the north wind came blowing fine dust along the frozen street, stinging one's nose and ears until they ached.

The company was billeted in the Piffre factory, which had a large yard, where the troops drilled. Normally we had drill and training lectures on one day, and a route march on the next. These marches were highly scientific affairs. In front strode McQueen, his hands behind his back. As he is unable to take a pace of less than a

yard and a half, he finds it extremely difficult himself to keep in step with the men

'Behind McQueen paced Charlie, who commands No 1 Section, holding a watch in front of him, and counting out loud, 'Twenty, twenty-one, twenty-two' and so on. 'we're only doing 106 to the minute now, sir,' Charlie would say. 'Quicken it up to 110 then,' says McQueen. 'That 's what we ought to be doing. ' So No1 Section swings at another four to the minute, Sapper Donnelly, as usual, leading the singing:

What's the use of worrying? It never was worth while. · So pack up your troubles

In your old kit bag,

And smile! smile! smile!

Damn,' says Charlie to himself under his breath, 'we're still only doing 108.' Then 'Quicken up the step a bit,' to Lance Corporal Bates or Corporal Virgo, who is leading the section behind him. A few minutes later, up runs Slattery from No 4 Section, panting, very red in the face, and considerably short in the temper, from having run the whole length of column, with his haversack and water-bottle beating against his legs. 'What the devil do you think you're doing?' gasps Slattery angrily. 'I suppose you know we've all been at a steady double at the back of the column, the whole way up the hill. 'Charles looks embarrassed, adjusts his glasses and says mildly, 'Well, I'm only doing 108 as it is.' 'Well for Heaven's sake go slower,' retorts the irate Slattery. 'It's all very well for you in front.' He had, indeed, hit upon one of those natural phenomena, which science seems powerless to explain - if the front of a column is marching at four mile, per hour, the rear is always at a steady run!

What's the use of worrying? It never was worth while. · So pack up your troubles

In your old kit bag,

And smile! smile! smile!

Damn,' says Charlie to himself under his breath, 'we're still only doing 108.' Then 'Quicken up the step a bit,' to Lance Corporal Bates or Corporal Virgo, who is leading the section behind him. A few minutes later, up runs Slattery from No 4 Section, panting, very red in the face, and considerably short in the temper, from having run the whole length of column, with his haversack and water-bottle beating against his legs. 'What the devil do you think you're doing?' gasps Slattery angrily. 'I suppose you know we've all been at a steady double at the back of the column, the whole way up the hill. 'Charles looks embarrassed, adjusts his glasses and says mildly, 'Well, I'm only doing 108 as it is.' 'Well for Heaven's sake go slower,' retorts the irate Slattery. 'It's all very well for you in front.' He had, indeed, hit upon one of those natural phenomena, which science seems powerless to explain - if the front of a column is marching at four mile, per hour, the rear is always at a steady run!

4-8 February: Route marches and drills on alternate days - Ground frost bound and no Coy training done, except as above. Lectures by O.C. Sections and by O.C. On work in general, demolitions, bridging. Orders received on 3rd for Coy with B Echelon 7 Co (300 men working party moving under orders O.C. 7 Field Company RE) to be prepared to take over maintaining and operate the "forward" portions of 60 cm Light Railway, at that time in the hands of the French in the area to be taken over by the III Corps immediately S. of the R.Somme. O.C with Lt Sidebottom and Lt Glubb went over all these lines (about 16 miles) on the 4th and 6th and arrangements made to take over as soon as possible after the 9th - on the 7th O.C visited III Corps HQ seeing C.E. (Bde Gen Schneider) + G & Q staff. The forward lines operated entirely by French Corps Artillery for artillery supply purposes. 3 petrol tractors brought from the III Corps area sent to La Flaque for use later instead of horse draught.

8 February: Fatigues and loading up for marching on 9th

9 February: Marched Chuigmes arriving 2pm. Huts taken over from French Battalion in the Bois Des Lapins.

10 February: O.C. took certain officers of B Echelon over the forward lines, all the maintenance and control districts acquired dugouts to take 3 platoons of B Echelon - returned to camp at 6pm to find that Capt Glubb had received orders to march 7 Field Coy and B Echelon to Mericourt Sur Somme at once. Information received on same day to effect that III Corps had decided to form under the A.D. Transportation operational Coy & 2 construction Coys. Possible railway and other personnel taken from the Corps - using existing personnel of B Echelon as far as possible -- Officers and other personnel of B Echelon recommended for permanent assignment on Lt Railways.

Merricourt Sur Somme, 11 February: O.C ordered to attend course for RE Field Company Commanders at Hesdin 13-24 and left same evening - Coy remained waiting orders.

12 February: Drills, kit inspection etc.

13 February: Route March, Mounted Section - Mounted drill.

14 February: Marched 8.45 am, reaching Foucaucourt. 11 am, to rejoin 50 Division - Sappers to huts immediately E of Foucaucourt, Mounted Section temporary at Proyart.

15- 16 February: Improvements to billets, rifle inspections etc. Mounted Section moved to near Rainscourt and work commenced on new stables.

17 - 19 February: Div order received, Coy placed at disposal of O.C. 7 D.L.I. (pioneers) for work on road making, work commenced on new Divisional Baths 1 mile. W of Foucaucourt - 2 Sections employed, 1 Section remained for work on tramways.

20 February: No 2 Section to Estrees work on dugouts - move later cancelled - work on Divisional Baths, Divisional hutting.

21 February: No4 Section Divisional Baths - No 2 Section commenced making huts in Foucaucourt (trench huts containing 120-130 Men each) Long trench steel shelter dugouts put up for Driver Section (No 3 Sect)

22-23 February: as above - inspection and certain work at ? under Lt Bruce RE

24 February: as above also erection of Nissen huts at P.C Gabrielle at Div HQ (No1 Sect)

25-26 February: as above Nissen hut erection completed 26th.- Officers hut at Foucaucourt (No 2 Sect) completed 26th - O.C. returned from course of instruction at Hesdin 26th

27-28 February: as above

8 February: Fatigues and loading up for marching on 9th

9 February: Marched Chuigmes arriving 2pm. Huts taken over from French Battalion in the Bois Des Lapins.

10 February: O.C. took certain officers of B Echelon over the forward lines, all the maintenance and control districts acquired dugouts to take 3 platoons of B Echelon - returned to camp at 6pm to find that Capt Glubb had received orders to march 7 Field Coy and B Echelon to Mericourt Sur Somme at once. Information received on same day to effect that III Corps had decided to form under the A.D. Transportation operational Coy & 2 construction Coys. Possible railway and other personnel taken from the Corps - using existing personnel of B Echelon as far as possible -- Officers and other personnel of B Echelon recommended for permanent assignment on Lt Railways.

Merricourt Sur Somme, 11 February: O.C ordered to attend course for RE Field Company Commanders at Hesdin 13-24 and left same evening - Coy remained waiting orders.

12 February: Drills, kit inspection etc.

13 February: Route March, Mounted Section - Mounted drill.

14 February: Marched 8.45 am, reaching Foucaucourt. 11 am, to rejoin 50 Division - Sappers to huts immediately E of Foucaucourt, Mounted Section temporary at Proyart.

15- 16 February: Improvements to billets, rifle inspections etc. Mounted Section moved to near Rainscourt and work commenced on new stables.

17 - 19 February: Div order received, Coy placed at disposal of O.C. 7 D.L.I. (pioneers) for work on road making, work commenced on new Divisional Baths 1 mile. W of Foucaucourt - 2 Sections employed, 1 Section remained for work on tramways.

20 February: No 2 Section to Estrees work on dugouts - move later cancelled - work on Divisional Baths, Divisional hutting.

21 February: No4 Section Divisional Baths - No 2 Section commenced making huts in Foucaucourt (trench huts containing 120-130 Men each) Long trench steel shelter dugouts put up for Driver Section (No 3 Sect)

22-23 February: as above - inspection and certain work at ? under Lt Bruce RE

24 February: as above also erection of Nissen huts at P.C Gabrielle at Div HQ (No1 Sect)

25-26 February: as above Nissen hut erection completed 26th.- Officers hut at Foucaucourt (No 2 Sect) completed 26th - O.C. returned from course of instruction at Hesdin 26th

27-28 February: as above

6 February : Went over with McQueen, Sidebottom and Rimbod, to see the French trench tramlines, which we are to take over. McQueen had been over before and, after going round the line, had a meal with a French Captain in his dugout. When they were going away, this officer asked Rimbod if he would send off a telegram for him on his way back. He handed him a telegraph form, saying, 'Arrive home tomorrow night' , and addressed to his wife in Paris. Rimbod congratulated him and asked him how much leave he had got; 'Well,' he replied, 'I'm not exactly going on leave, but now that I have shown you people over, no one will miss me for a week or so!'

We were promised 'al car by the corps to take us over to see the French, but, when it rolled up, it turned out to be a water-tank lorry! So while McQueen sat in front by the driver, Rimbod, Sidebottom and I clung precariously on top of the water tank, frozen perfectly stiff. Drove over via Bray-sur-Somme to Chuignes!(Our camp is to be in Adrian huts, in a wood called the Bois des Lapins, just beyond Chuignes. It is at present occupied as a reserve camp by a battalion of French infantry. A tall fair-haired commandant with long fair moustaches showed us round. Their men, I noticed, were very untidy and dirty, and showed no respect for their officers, even talking to them sitting down with cigarettes in their mouths. The commandant addressed me as 'le jeune homme', and refused to believe I was a captain, as I looked so young.

We were promised 'al car by the corps to take us over to see the French, but, when it rolled up, it turned out to be a water-tank lorry! So while McQueen sat in front by the driver, Rimbod, Sidebottom and I clung precariously on top of the water tank, frozen perfectly stiff. Drove over via Bray-sur-Somme to Chuignes!(Our camp is to be in Adrian huts, in a wood called the Bois des Lapins, just beyond Chuignes. It is at present occupied as a reserve camp by a battalion of French infantry. A tall fair-haired commandant with long fair moustaches showed us round. Their men, I noticed, were very untidy and dirty, and showed no respect for their officers, even talking to them sitting down with cigarettes in their mouths. The commandant addressed me as 'le jeune homme', and refused to believe I was a captain, as I looked so young.

Albert, 1 - 3rd February: Route marches on 1st & 3rd.- drills on the 2nd, lectures by Section officers, after drills.

The French tramway system is, of course, entirely different to ours, which does not facilitate taking over. The French tramways are solely used for artillery ammunition,

whereby they miss an enormous field of utility in supplying their infantry. Hence their lines run up only as far as the guns. The tramway personnel are all garrison gunners, organized in companies. These are composed of professional railwaymen and the lines are organized like a little railway system. We, who have been told to take over, have not a single officer who has ever been on a railway, no tools, equipment or skilled men. We were originally chosen for our rapidity in laying down and bolting together ready made rails, in the dark and under shell fire. Square pegs in round holes aren't in it. .

Of course in our future camp there is no stable. It makes me angry when people say of the horses, 'Stick them out there in the field', but horses cannot speak and so get no consideration. Yet we are constantly receiving orders about, the shortage of horses and the need to care for them. After seeing the camp we went round some of the French lines, and looked into a couple of dugouts occupied by French N.C.O.'s. On the way back, we called on a lieutenant, who lived in a little hut which was wall papered, 'furnished and hung with pictures. He insisted on speaking English, almost unintelligibly, though he thought he spoke like a native. It is lucky for our peace of mind that we can never tell how badly we speak a foreign language. After this, back to Albert on our icy water tank .

8 February: We leave Albert tomorrow. The horses are still at Becourt, but I have had the wagons all brought in here during the last few days. The sappers washed them in the river, and they were then painted all over with wagon preserving oil, so we ought to look nice on the march tomorrow.

9 February: The horses came in from Becourt this morning, and hooked into the wagons which were waiting for them in Albert. I stood waiting for them at the bend of the Rue des Illieux, when I suddenly heard the clicking of hoofs and the jingling of harness coming from the Rue de Bapaume. I don't think I shall ever forget seeing them come round the corner into view, Enderby in front with his pair of horses, Michael and Farmer, the steelwork of their harness gleaming like silver, a new green canvas bucket swinging from his saddle. Behind him the long line of horses, their chains and traces swinging in and out. Here they come, my old pairs of horses and my boys! The company looked perfect, swinging out on to the bleak, bitter downs on the road to Bray, the sappers with lean shining badges, the horses with glossy coats, almost black-looking oil-softened leatherwork, and steelwork gleaming like silver.

Soldiers are notorious for the number of pets they collect, and we are no exception, especially the mounted section.The oldest inhabitant in this category is a little Yorkshire terrier called Nobby, having been the property of Nobby Clark. He is a funny little fellow, though very plucky and used to lead the company last autumn, trotting along about ten yards in front. This time the lead was taken by Monty, so called because he was born at Mont des Cats, a little brown and black dog. Another old stager is a little fox terrier bitch called Nellie, who belongs to the drivers. In spite of orders circulated at intervals for the destruction of all stray dogs, Nellie invariably marches with us, perched on top of the front of one of the pontoons, where she has been much admired. Though the old boats sway a good deal, she never seems to lose her balance, but stands looking at the view, her ears alertly pricked all the way.A rumour having reached us that the camp allotted to us at Bois des Lapins was still occupied by a French battalion, McQueen took me on ahead with him to see. I hated this, because one so rarely gets a chance of seeing one's fellows on the march, and because it did not seem to me the game for the two senior officers to ride on ahead, while the boys slog it along the road in a biting wind. Arriving at Bois des Lapins, the rumour proved correct, the French not intending to move till next day. They were vastly amused at our being on the road, and said something ill-mannered about British staff arrangements. They were not keen to be of any assistance, but pointed to two