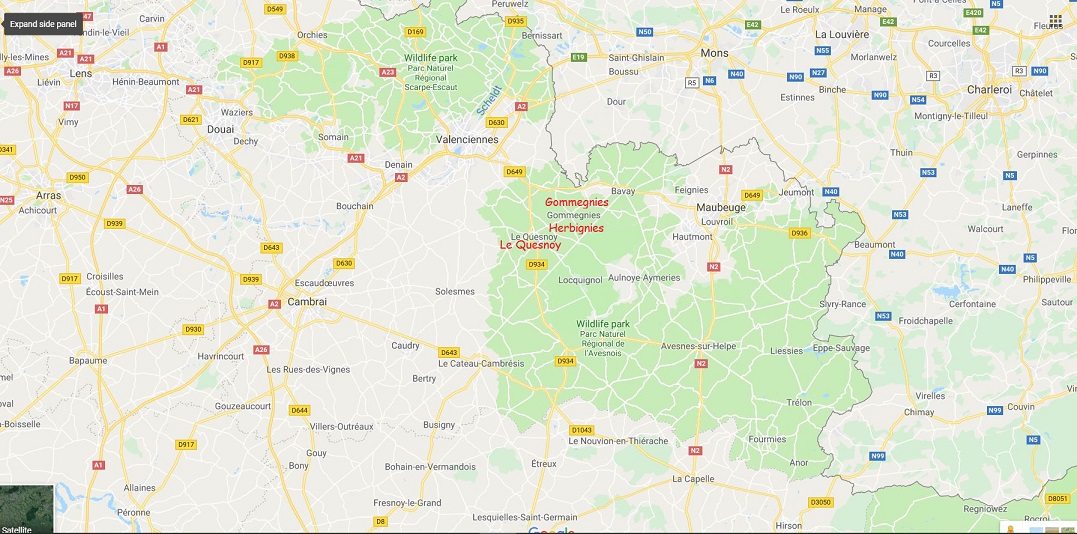

7 Field Company Royal Engineers 1919

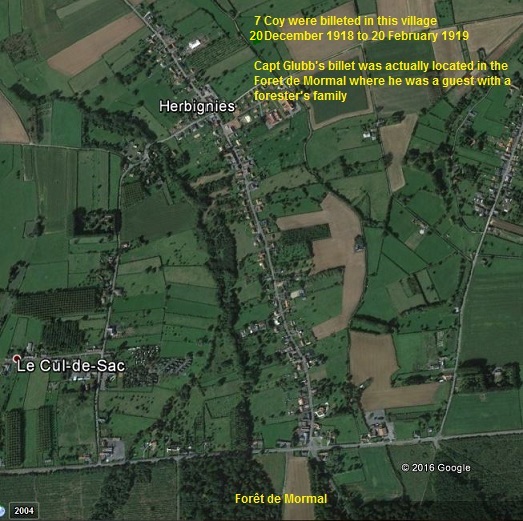

Herbignies

1-31 January 1919: Demobilising and overhauling of stores and equipment. Parties attached to 149th Brigade HQ, 3rd RF, 2nd RF and 13th R.H. for repair of billets and demolition of dud shells. Party at Gommmegnies in charge of RE Dump.

Herbignies

1-20 February 1919: Demobilising, repair work at Le Quesnoy overhauling stores and equipment

21 February: Coy moved to Le Quesnoy by road.

22-28 February: At Le Quesnoy. Repair work on billets and recreational halls

Le Quesnoy

1-31 March 1919: Company situated in Le Quesnoy and employed upon general repair of billets in the town --- checking and controlling of mobilization stores and reduction to Cadre A of regular personnel and animals. Reduced to Cadre A at segments, men 18th day and as regards animals 25th day.

Capt M.H. King took over command of Company upon transfer of Major J McGill RE to the Rhine upon 18.3.19.

Le Quesnoy

1-30 April 1919: The Company engaged on works in Le Quesnoy, running electric lightening sets and providing guards over RE Dumps in the vicinity of Le Quesnoy

7 April: Lt, acting Capt King M.H. Transferred to 288th Army Troops Coy RE.

Lt S. Wilson RE from 447 Field Coy RE took over command of the Company.

22 April: Two copies of AFG1098 taken into use according to instructions in demob instructions France part 1

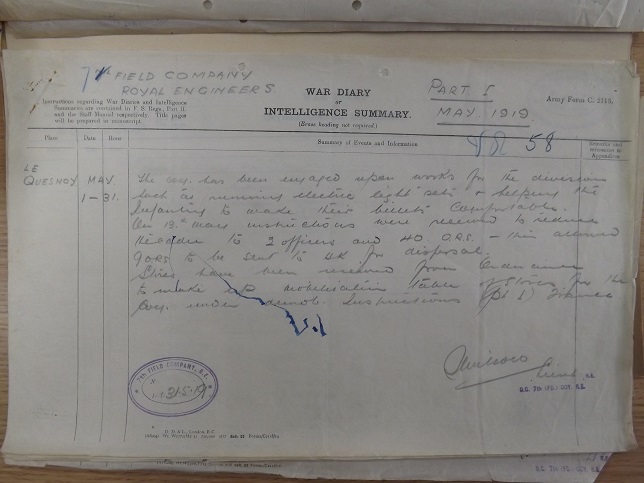

Le Quesnoy

1-31 May 1919: The Coy has been engaged upon works for the Division, such as running electric light sets and helping the infantry to make their billets comfortable.

On 13th May instructions were received to reduce the cadre to two officers and 40 O.Rs -- this allowed 9 O.Rs to be sent to UK for disposal. Stores have been received from ordenance to make up mobilization table of stores for the Coy, under demob. Instructions part 1 France.

Army of occupation By Capt H.A. Baker MC.

The Company was finally reduced to cadre strength of 2 officers and 40 other ranks in May 1919. Early in 1920 it was decided to form a company to send to the Army of Occupation at Cologne and

the 7th Field Company was reformed in Chatham. Lieut H.A. Baker, M.C. who had served with the Company during the war, was appointed to form the Company. The only other member of the wartime Company was Driver ‘’Knobby’’ Clark, who served throughout the war as O.C.’s batman. The Company proceeded to Cologne in April 1920, and was there, handed over to the command of

Bt. Major Wilson ,D.S.O., finally returning to Colchester to its old Division in 1929, when the Army of Occupation was withdrawn.

The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 to 1919 (from historic-uk.com)

By Ben Johnson

"I had a little bird

its name was Enza

I opened the window,

and in-flu-enza."

(1918 children’s playground rhyme)

The ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic of 1918 was one of the greatest medical disasters of the 20th century. This was a global pandemic, an airborne virus which affected every continent.

It was nicknamed ‘Spanish flu’ as the first reported cases were in Spain. As this was during World War 1, newspapers were censored (Germany, the United States, Britain and France all had media blackouts on news that might lower morale) so although there were influenza (flu) cases elsewhere, it was the Spanish cases that hit the headlines. One of the first casualties was the King of Spain.

Although not caused by World War I, it is thought that in the UK, the virus was spread by soldiers returning home from the trenches in northern France. Soldiers were becoming ill with what was known as ‘la grippe’, the symptoms of which were sore throats, headaches and a loss of appetite. Although highly infectious in the cramped, primitive conditions of the trenches, recovery was usually swift and doctors at first called it "three-day fever".

The outbreak hit the UK in a series of waves, with its peak at the end of WW1. Returning from Northern France at the end of the war, the troops travelled home by train. As they arrived at the railway stations, so the flu spread from the railway stations to the centre of the cities, then to the suburbs and out into the countryside. Not restricted to class, anyone could catch it. Prime Minister David Lloyd George contracted it but survived. Some other notable survivors included the cartoonist Walt Disney and Kaiser Willhelm II of Germany.

Young adults between 20 and 30 years old were particularly affected and the disease struck and progressed quickly in these cases. Onset was devastatingly quick. Those fine and healthy at breakfast could be dead by tea-time. Within hours of feeling the first symptoms of fatigue, fever and headache, some victims would rapidly develop pneumonia and start turning blue, signalling a shortage of oxygen. They would then struggle for air until they suffocated to death.

Hospitals were overwhelmed and even medical students were drafted in to help. Doctors and nurses worked to breaking point, although there was little they could do as there were no treatments for the flu and no antibiotics to treat the pneumonia.

During the pandemic of 1918/19, over 50 million people died worldwide and a quarter of the British population were affected. The death toll was 228,000 in Britain alone. Global mortality rate is not known, but is estimated to have been between 10% to 20% of those who were infected.

More people died of influenza in that single year than in the four years of the Black Death Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351.

By the end of pandemic, only one region in the entire world had not reported an outbreak: an isolated island called Marajo, located in Brazil's Amazon River Delta

7 Field Company's main movements in the 1920s:

Date Place Event

April 1920 Company re-formed at Chattenden

April 1920 Cologne as part of the British Army of the Rhine

Nov 1929 Return to UK, Colchester

Demobilisation and discharge

Procedure

The process and timing of the demobilisation of a soldier after the war depended on his terms of service. Soldiers of the regular army who were still serving their normal period of colour service remained in the army until their years were done. Men who had volunteered or who were conscripted for war service generally followed the routine described below. Although pretty well everyone wanted to go home at once, it was simply not possible. Not only would it have been practically impossible to process all men in a short period of time but the British army still had commitments it had to fulfill, in Germany, North Russia and in the garrisons of Empire. Men with scarce industrial skills (including miners) were released early; those who had volunteered early in the war were given priority treatment, leaving the conscripts - particularly the 18 year olds of 1918 - until last. Even so, most of the war service men were back in civilian life by the end of 1919.

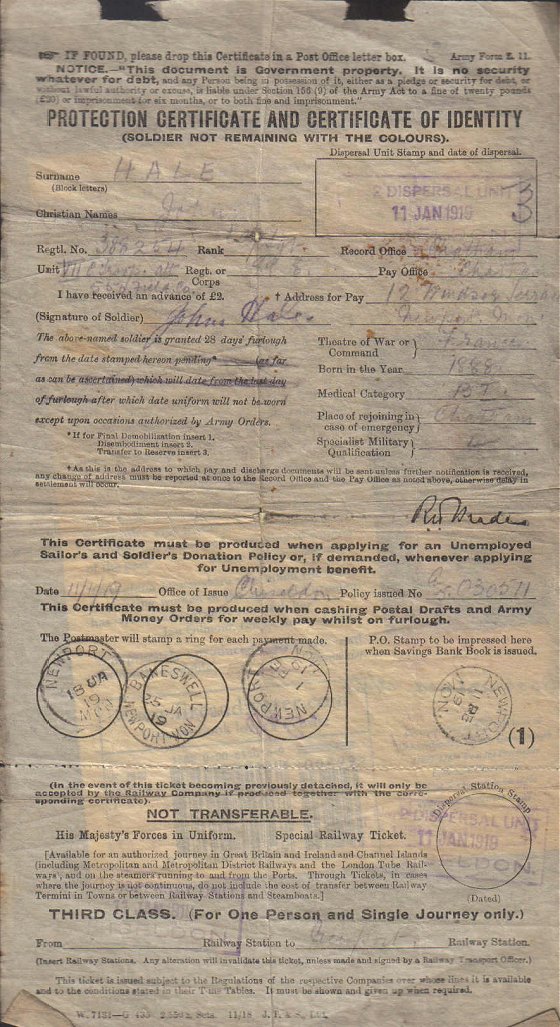

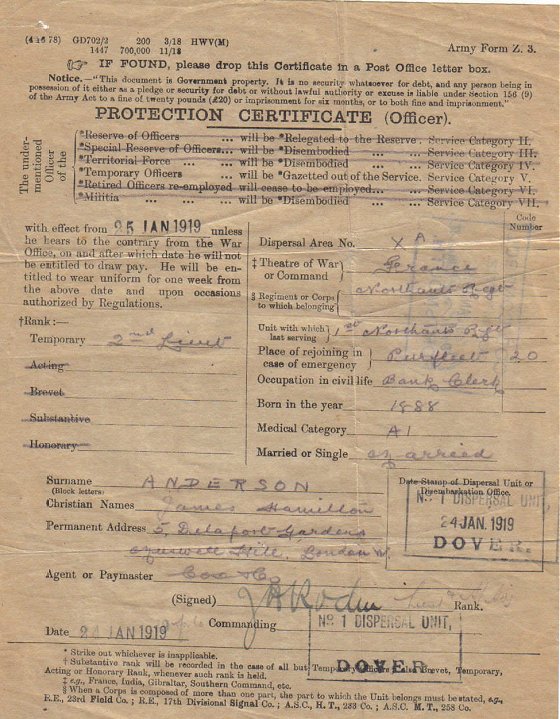

Before the soldier left his unit he was medically examined and given Army Form Z22, which allowed him to make a claim for any form of disability arising from his military service. He was also given an Army Form Z44 (Plain Clothes Form) and a Certificate of Employment showing what he had done in the army, Z18. A Dispersal Certificate recorded personal and military information and also the state of his equipment. If he lost any of it after this point, the value would be deducted from his outstanding pay.

He was not allowed to bring back to the UK any Belgian or locally issued French banknotes. Official government-issued French or Italian banknotes could be taken home and exchanged for Sterling at a Post Office. If he was returning from any other theatre of war he had to change the local currency into a Postal Order at an Army Post Office. The soldier would spend some time in a transit camp - an Infantry Base Depot - near the coast before being warned for a homeward sailing.

On arrival in England the man would move to a Dispersal Centre. This was a hutted or tented camp or barracks. Here he received a Z3, Z11 or Z12 Protection Certificate and a railway warrant or ticket to his home station. This certificate enabled the man to receive medical attention if necessary during his final leave.

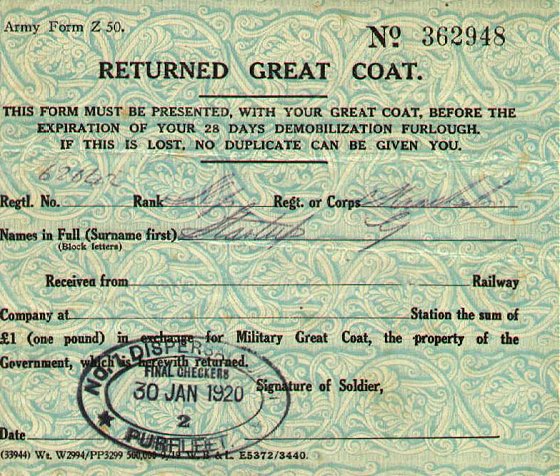

He got too an Out-of-work Donation Policy, which insured him against unavoidable unemployment of up to 26 weeks in the 12 months following demob. He received in addition an advance of pay, a fortnight's ration book and also a voucher - Army Form Z50 - for the return of his greatcoat to a railway station during his leave. He could choose to have either a clothing allowance of 52 shillings and sixpence or be provided with a suit of plain clothes. If he chose the latter he would hand in his Z44. His final leave began the day after he was dispersed. He left to go home, still in uniform and with his steel helmet and greatcoat.

While on final leave he was still technically a soldier although could now go about in plain clothes. Legally he could not wear his uniform after 28 days from dispersal. During leave he had to go to a railway station to hand in his greatcoat. For this he was paid £1. This was counted as part of his war or service gratuity payment. Any other payments due to him were sent in three instalments by Money Orders or Postal Drafts. These could be cashed at a Post Office on production of the Protection Certificate. The man could also take his Demobilisation Ration Book to the nearest Food Office and exchange it for an Emergency Card, which he could later exchange for a civilian Ration Book.

Some men could claim repatriation to an Overseas British Possession or a Foreign Country. The man completed Army Form AF.Z7 to do this.

As long as the Military Service Act was enforced, all men who was liable for service under the Act who was not remaining with the colours in the regular army; or who had not been permanently discharged; or who was not on a Special Reserve or Territorial Force Reserve engagement was discharged into Class Z Army Reserve and liable to recall in the event of a grave national emergency. His designated place of rejoining was shown on his Protection Certificate and Certificate of Final Demobilisation

Last page of 7 Field Company's World War One War Diary

Above: This "other ranks" Z11 Protection Certificate was kindly provided by Graham Stewart. This soldier was being demobilised at Chiseldon Camp in Wiltshire in January 1919. Note the three Post Office rubber stamp marks, denoting his visits to pick up his final pay.

The above article including the three Army Forms are by kind permission Chris Baker on behalf of Milverton Associates Limited.

For more information on the above and many other subjects on WW1. Click on this link to

"Chris Baker's" site: The Long, Long Trail https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/

British soldiers handing in their rifles before boarding ship for home.

In November 1918, the British army had numbered almost 3.8 million men. Twelve months later, it had been reduced to slightly less than 900,000 and by 1922 to just over 230,000.

Misery in the Mud

Life in the trenches was nightmarish, aside from the usual rigors of combat. Forces of nature posed as great a threat as the opposing army. Heavy rainfall flooded trenches and created impassable, muddy conditions. The mud not only made it difficult to get from one place to another; it also had other, more dire consequences. Many times, soldiers became trapped in the thick, deep mud; unable to extricate themselves, they often drowned.

The pervading precipitation created other difficulties. Trench walls collapsed, rifles jammed, and soldiers fell victim to the much-dreaded "trench foot." A condition similar to frostbite, Trench Foot developed as a result of men being forced to stand in water for several hours, even days, without a chance to remove wet boots and socks. In extreme cases, gangrene developed and a soldier's toes -- even his entire foot -- would have to be amputated.

Unfortunately, heavy rains were not sufficient to wash away the filth and foul odor of human waste and decaying corpses. Not only did these unsanitary conditions contribute to the spread of disease, they also attracted an enemy despised by both sides -- the lowly rat. Multitudes of rats shared the trenches with soldiers and, even more horrifying, they fed upon the remains of the dead. Soldiers shot them out of disgust and frustration, but the rats continued to multiply and thrived for the duration of the war. Other vermin that plagued the troops included head and body lice, mites and scabies, and massive swarms of flies.

As terrible as the sights and smells were for the men to endure, the deafening noises that surrounded them during heavy shelling were terrifying. In the midst of a heavy barrage, dozens of shells per minute might land in the trench, causing ear-splitting (and deadly) explosions. Few men could remain calm under such circumstances; many suffered emotional breakdowns.

The Legacy of Trench Warfare

Due in part to the Allies' use of tanks in the last year of the war, the stalemate was finally broken. By the time the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, an estimated 8.5 million men (on all fronts) had lost their lives in the "war to end all wars." Yet, many survivors who returned home would never be the same again, whether their wounds were physical or emotional.

By the end of World War I, trench warfare had become the very symbol of futility; thus, it has been a tactic intentionally avoided by modern-day military strategists in favor of movement, surveillance, and airpower

Video: 7 Field Company's Final Locations of World War One. Epehy to Semousies and the Winding Down of the Company in 1919. https://youtu.be/iP5MmtaVvXw

Read Philip Gibbs account on the occupation of the Rhineland December 1918:

http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/rhineoccupation_gibbs.htm

Feedback welcome: georgecowie103@yahoo.co.uk

Captain Glubb MC, final diary entry.